GLADIATORS and the ARENA

The Entertainment and Games of Rome

Information on Gladiatorial Combat and the Great Colosseum and maybe some answers to questions you did not know to ask.

A Page dedicated to the "Ludus Magnus and Gladiatorial Academia", which was formally an unit of Legion XXIV, but is now a separate allied organization.

May 1, 2015

LUDUS MAGNUS GLADIATORES

John Ebel - Maximus Mercurius Gladius - Summus-Palus (Highest in the Post) and Founder lycanthrope1@optonline.net 631-379-3872

Albert Barbato - Aulus Scipio Barbatus - Summus-Palus (Highest in the Post) - Co-Founder aliebeee@optonline.net

Secutor versus Retiarius

"Ave Imperator; Morituri te Salutant!"

Hail Emperor; Those who are about to die Salute Thee!

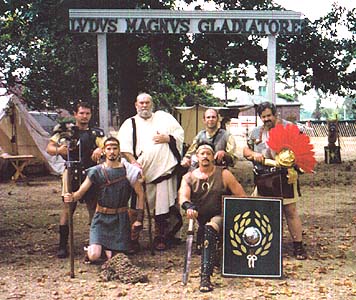

The Ludus Magnus participants at Eisenhower Park, Long Island, NY Aug 6, 2001

Kneeling Left - Joseph Abbondonelo "Quintus Virilis Lucan" (Retarius, Net & Trident) - Kneeling Right - John Ebel "Maximus Mercurius Gladius" (Lead Gladiator) - Standing Left to Right - Kryn Minor "Cascus Tiberius Rufio Longinus" (Cmndr Leg-VI) - James Matthews "Marcus Minicius Audens" (Leg-XXIV, Lanista-Senator) - Brian Helt "Titus Ausonius Italicus" (Leg-VI) - Mike Catellier "Lupus Britanicus" (Leg-VI, Wolf of Britannia).

Legion XXIV Soldiers, Civilians and Ludus Magnus Gladiators assemble in the Courtyard of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology in Philadelphia on March 16, 2003. Legion XXIV and the Ludus were there to assist the Museum (UPM) with the "Return to Rome" Gala Re-Opening of their Roman, Greek and Etruscan Galleries after a decade long refurbishment and expansion. Click on the photo for more pictures and details.

Ludus Magnus in the Great Arena

"Maximus" displays his line-up of veteran and neophyte "tyro" gladiators in the entrance courtyard of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology in Philadelphia, on March 16, 2003. The Ludus Magnus staged seven gladiatorial engagements in conjunction with the public opening of the Museum's New Etruscan and Roman Galleries. Some 3000 observed the "Ludus" in action during the day.

Maximus Gladius, "Palus Primus" (lead gladiator) demonstrates a sword thrust to the "Palus"(practice) post; as Lupus Britanicus (Wolf of Britannia), at right; and Titus Italicus, Gallio Marsallas and "Procuratore" Marcus Audens look on.

Gladiatorial Games were Etruscan in origin and the first gladiatorial combat took place in Rome in 264 BC. During Etruscan funeral masses, two warriors "bustiarius" would fight over the grave of the deceased in a display to honor the dead. This Etruscan tradition later came to Rome, also as a funeral ceremony. At first, gladiatorial combat was only a matter of a few prisoners of war or criminals facing each other in contests staged at the funerals of distinguished Romans. Events were also staged involving animal combat and beast hunts "Venatio" to honor the gods Flora and Ceres and chariot races became popular during festivals in honor of the god Mars; in which the winning horse would be sacrificed. But, by the time of Julius Caesar, any connection of these brutal contests with funerals and religious festivals was long gone and they had become public spectacles similar to our modern football games, rodeos, boxing and wrestling matches.

The greatest number of "Games - Ludi" were staged under the rule of Augustus (27BC - 14AD). During this period, due to a dearth of warfare, the masses became bored and the spectacle of the "Games" served to remind them of the victorious battles that had brought Rome to Her Glory. Also, the brutality of the Arena may have made the lives of the common people seem easier and less severe by comparison. To us, gladiatorial events may now seem repulsive; but for the people of Ancient Rome, the "Games" were something they loved and needed. The "Animal - Venatio / Bestiarium" events were meant to reinforce the belief in the superiority of Man (and Rome) over Beasts and Nature; while the Gladiatorial Combats demonstrated the courageous virtues of the Roman Soldier, and of Rome itself. During the Games, numbered wooden balls "missilia" would be thrown into the crowd to be redeemed later for prizes.

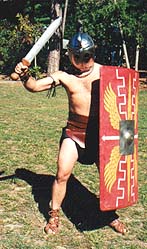

John Ebel (Maximus) confronts Michael (Lupus) Catellier, at the Roman Days encampment in Glendale, MD, on June 9, 2001. Maximus Wants You! in his Gladiatorium Academia.

Many gladiators used, or were given nicknames; which helped to mask their less than honorable status, as most were condemned men. Some gladiators were professionals, some were slaves, many were captives and prisoners of war; but together in combat in the amphitheaters and arenas they became symbols of Rome's control over the ancient world. Not to be confused with the gladiatorial games "munus gladiatorium" and their exhibition of combat was the execution of criminals "noxii" and others charged with the most serious offences. Condemned "damnatio" to die as a lesson to others, they were brutally killed "necare" in the most public of spaces, the circuses and amphitheaters. In front of tens of thousands of spectators, they were burnt "comburere", crucified "cruce suffregeri", put to the sword "damnati ad gladium" or exposed defenseless to the savagery of wild beasts "damnati ad bestius" or as untrained slaves or criminals "gladiatores meridiani" were forced to fight and execute one another. Some of these were Christians, who faced death for the treasonable offence of refusing to sacrifice to the will of the Emperor, thereby rejecting the Roman and state-sanctioned religion of Paganism. Noxii could also be sentenced to a gladiator school "damnati in ludum" to be trained to fight (and probably die) in the Arena.

As "Thracian" was set against "Mirmillo" and "Secutor" faced "Retiarius" in these contests of life and death, their fate was determined by a gesture of the Emperor's hand; which might be influenced by the verdict of the crowd. The spectators expected and applauded a close-fought and exciting battle; which demonstrated the Roman affection for warlike spirit and courage. Bravery was the foremost virtue of the Romans, who valued military service above the athletic achievements of the Greeks. Gladiatorial combat focused public attention on the ultimate expression for a Roman man: That of Courage, Stoicism and Bravery.

During Roman Days - 2003, the Barbarian "Wolf of Britain" (left) was confronted by "Retiarius" styled Aulus Scipio Barbatus. The "Wolf" came out victorious. Barbatus, survived however, to later avenge his defeat.

Spectacular entertainment for the masses and the exercise of political power were the hallmark of the Roman Imperial Era. "Bread and Circuses" (Panem et Circences) were what the Roman people demanded of their Emperor in a reciprocal relationship that generally suited both parties well. Giving to Receive "Euergetism" was a well established practice of the power brokers of the Roman world and to receive the loyal support of the people, these "Leaders" gave them spectacular games, spectacles and entertainment "munus - a gift or favor of entertainment" from the First Century BC to the end of the Fourth Century AD.

Gladiators or "Sword Men" got their name from the "Gladius" or 27 inch short sword carried by roman solders and also used by the fighters in the arena. "Gladius" was also a vernacular latin term for the penis and in popular imagination many gladiators were thought to be symbols of virility. Women were said to covet the sweat of gladiators as an aphrodisiac. Many gladiators became popular and wealthy with their flamboyant personalities and fighting prowess in the arena; much like the wrestlers, boxers and sports stars of today.

"Barbarian" Lupus Britanicus, takes on "Samnite" Maximus Gladius. Note the "Palus" practice posts to rear.

The culture that produced the gladiators also created the

atmosphere that eventually led to their extinction in the early 4th century

AD. After the conversion of Constantine "the Great" to Christianity

and his coming to power as Emperor in 312 AD; he issued an edict abolishing

gladiatorial combat in 323; but was unable to completely suppress the games.

Although Christianity had been established as the official state religion of the Roman

Empire, in 312; it would be 92 years before gladiators were finally abolished.

In AD 404 a tragic event finally put an end to the gladiators. A

Christian monk named Telemachus jumped into an arena in Rome and tried to separate two

combatants. The crowd went berserk, climbed over the walls into the arena and

tore the monk limb from limb. In response to this ugly incident, the Emperor

Honorius permanently banned all gladiator contests. Unlike Constantine,

he enforced the ban. The era of the gladiator was over. The creed

of Christianity was primarily responsible for bringing an end to gladiatorial combats.

Violence and cruelty have continued to be all too common in world history, but never

again have amphitheaters been filled with crowds of people gathered to watch men who were

expected to maim or kill each other for sport and entertainment.

While it has been 1600 years since the last gladiator walked into the arena, many

elements of their games are alive and well today. The elements of the Roman

gladiatorial games can be readily recognized in the football, hockey, western

rodeo, bull-fights, boxing and wrestling matches conducted today; where the

participants don armor, employ game weapons, assume colorful names and titles and in many

instances, gain great popularity and wealth. Women would collect the

sweat of famous gladiators as an aphrodisiac.

Modern horse and auto racing events are not much different from what Roman citizens

witnessed in the Circus-Maximus in Rome, where with the same speed and excitement,

horses were raced "cursu equestri certare" and chariots

competed "curriculi" and collided for the enjoyment of the cheering crowds.

The heavy betting on the outcome of the races "certari" and

games "ludi" has hardly changed over the centuries.

Bulldogging, "Thessalonian (from Thessaly in Greece) bull-fighting"

where a bull is wrestled to ground by its horns, was introduced to Rome by

Julius Caesar. Almost every modern circus act was perfected in Rome, 2000 years before

P.T.Barnum and the Ringling Brothers were born. Trained lions and

tigers, dancing bears, acrobats, clowns and jugglers had the same attraction to

ancient Romans as they do to modern audiences today. It surely is true that history

repeats itself.

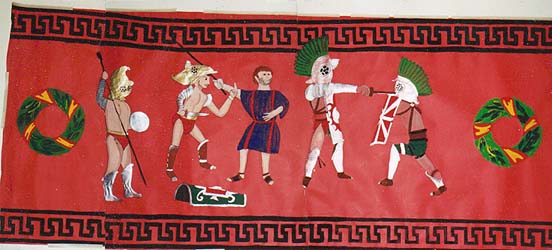

A tapestry of Gladiatorial figures created by Merlinia Ambrosia (Joanne Shaver) of the SCA Barony of Settmorr Swamp. The 4 x 10 foot piece was displayed at the "Roman Tavern Event", sponsored by the Barony's Canton of Gryphonwald, in Edison, NJ, on February 15, 2003.

STYLES OF GLADIATORS AND TYPES OF COMBAT

SAMNITE "Samnium" One of the first types of Gladiator, they took their name from the Samnites, which were among the earliest enemies of the emerging Roman dominance of northern Italy. They generally utilized heavy armor with a visored helmet, large scutum shield, wrist guards and a greave "ocrea" on the lower left leg. Samnites fought with the Gladius sword giving rise to the general of term of "Gladiator" being applied to most of those who fought in the Arena.

HOPLOMACHUS "Heavy Armor" This style of fighter was very similar to the Samnite. They were more heavily armored with a fully protected right arm, large shield, more massive helmet and more leg protection. It appears that the Hoplomachus was a later style of the Samnite and they also fought with the gladius. During the Republic "heavy" fighters were termed Samnites and in the Empire Period they became known as Hoplomachus.

Above is a Hoplomachus style gladiator helmet. Note the massive crest ridge. This style helm was also worn by Samnite "heavy" style fighters. Below is a Thracian style helmet. Note "gargoyle" like appearance and "griffin" adornment at the peak of the crest. Both of these helmet styles are the classic image of gladiator headgear.

THRACIAN "Light and Fast" These fighters depended on being more lightly armored and therefore more agile and faster in evading their adversary. Thracians utilized an unusual "Sica" curved style sword and a small round "parma" shield, along with large greaves on both legs which extended above the knees. They had no chest armor; but did have full right arm protection and a crested helmet. Some of the helmet crests were shaped like a Griffin, alluding to a mythological bird of prey.

Samnite Hoplomachus Thracian Murmillo

MIRMILLO / MURMILLO "Fish Man" With just right arm protection and a non-visored helmet, these gladiators were relatively unprotected; but were still considered "heavy" fighters due to the large and heavy shield they carried. They fought with a gladius style sword. The term of Mirmillo/Murmillo or Fish Man may have come from the fact that they were generally paired with the "Retarius" or Net Fighter who would attempt to catch his Fish Man opponent in his net and then stab him with his trident spear.

A "Mirmillo / Murmillo" or "Fish Man" style helmet, topped with a fish-like dorsal fin, on the left and a "Secutor" or "Chaser" style on the right. Note the smooth contours of the Secutor helmet that minimized its being snagged by the Retiarius' net, with whom the Secutor was usually paired. Also, the eye holes of the Secutor helmet were sized and spaced to make it difficult for the 3-pronged trident of the Retiarius to penetrate it. The Mirmillo was also often paired with the Retiarius; but his helmet with some sharp angles and corners would offer a better target for the Retiarius' net.

SECUTOR "Chaser" The technique of this fighter was to chase his opponent around the field of battle and exhaust him out for the kill. He wore a rounded crested helmet with small round eye holes. Although limiting vision, the small eye holes made it nearly impossible for the Retriarius' trident tines to penetrate to the Secutor's eyes. The smooth shape of the helmet, without any projections, was less likely to be come ensnared in the net thrown by the Retiarius; with whom he was generally paired for a fight. He had full right arm protection and wore an Ocrea or greave on the lower left leg. He also carried a large rectangular scutum shield.

RETIARIUS "Net and Trident" These fighters used the strategy of attempting to snare and entangle their opponent in the net that he would cast like a fisherman; and then stab him with the three-pronged "trident" spear he carried. The net had weights attached to the edges to assist in making the net flare-out when thrown. The net also had a tether cord attached so the Retiarius could draw it back if it failed to snare his adversary. The Retiarius wore no helmet or body armor; other than some left arm protection and a "Galerus" or large flared shoulder piece.

A Retiarius shown with Trident, Net and Galerus. Note "Squamata" (fish scale) "Manica" arm guard, decorated Galerus shoulder shield and safety covers on Trident points in right hand photo.

![]()

Secutor Dimacheri Provocateur Hermes Psychopompo "Mercury"

DIMACHERI "Two Handed" Gladiators who fought with two swords. This term can also be applied to those who fought from horseback.

EQUES / EQUITES "Equestrian" Those who fought "mounted", that is from horseback using various weapons.

LAQUEATORES "Noose-Snare" A variation of the "Retiarius" who attempted to use a spear and noose or lasso to snare their opponents.

ESSEDARIUS / ESSEDARII "Chariot Warriors" Combatants who rode chariots during their engagements.

ORDINARII "Ordinary" were gladiators who fought in pairs or in the ordinary manner.

ANDABATAE "Blinded" wore helmets with no eye apertures, thus they fought "blind" which was especially exciting to the spectators.

SAGITTARIUS An animal fighter armed with bow and arrow.

GLADIATRIX Female Gladiator - Who were especially popular with the crowds.

MERIDIANI "Median" were lightly armored fighters who fought in the middle of the day after the morning "Beastiary" engagements with wild animals had taken place.

CATERVARII "Crowd" A term applied when the combatants fought in a melee as a group or mob, instead of in pairs.

VENATIO / BESTIARIUM A show that often featured trained animals performing tricks, wild animal hunts, animals fighting each other or animals killing condemned criminals. Generally staged as a mid-day event prior to the main gladiatorial "munus gladiatorium" engagements.

MUNUS A favor or gift of public entertainment. "Munus-Gladiatorium" - a free or provided gift of a gladiatorial combat exhibition to the public by the leaders of Rome.

Array of Gladiatorial Equipment, Left to Right - Large scutum shield as used by the so-called "Heavy" fighters, Samnite, Hoplomachus, Thracian, Murmillo. - A Galerus shoulder & neck shield decorated with starfish and net, as used by the Retiarius. - Squamata (fish scale) style Manica arm guard. Segmentata (articulated plate) style Manica arm guard, with padding. - Undecorated medium size Parma style round shield. - Shoulder and upper chest armor (behind shield). - Secutor style helmet with small round eye holes. - Leg Greave -guard. - Retiarius Trident and Net, with round hilt sword in front. - Twin-bladed "Scissorarius" sword, resting against a Thracian scutum-shield, with Thracian helmet and referee's staff above. - Round Parma shield with Medusa image and two swords, a bottle and other small items above.

A gladiator would generally have his left leg extended forward when in his battle stance, hence he would only wear protection on his left leg and ankle. The Mirmillo and Retiarius generally wore no leg protection due to their fighting strategies. The Thracian, and at times, other gladiator styles as well, would wear greaves on both legs, with the left hand greave sometimes being more substantial than the one on the right leg.

Despite what Hollywood would have us believe, good and/or popular gladiators were seldom deliberately killed. They were too valuable to their owners and promoters; as much time, expense and effort had been expended in their training and preparation.

The Emperor's "thumbs-up" to "spare" or "thumbs-down" to "kill" is another mis-interpretation from Hollywood. In actuality, the proper sign is thought to have been "pollicis-deflectere - turned thumb" with the thumb turned sideways across or towards the chest, which indicated "stick it to him" or to "dispatch" the vanquished fighter with a sword thrust downward into the neck or upper back. The thumb held down upon the fist, "pollicis-demissus" is thought to have meant "mitto / missus- let go of" or "to spare" by indicating that the victorious gladiator should retire his weapon to the ground and withdraw from the engagement.

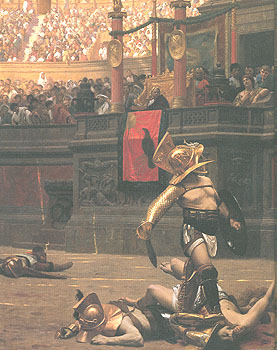

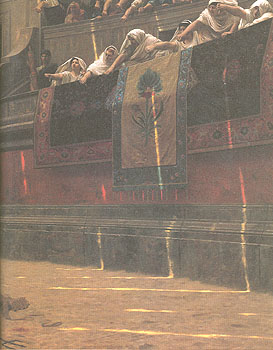

The origin of the "up-thumb" and

"down-thumb" is believed to have come from flawed translations of Greek

and Latin texts and the 1872 painting "Pollice Verso - Thumbs Down"

by the French painter Jean Leon Gerome, shown above. This famous rendering shows a

victorious Mermillo styled gladiator, with his foot on his fallen

opponent's throat, looking up to see the fatal gesture of "thumbs

down" being given by the the crowd surrounding the Emperor's Box, that

dooms his enemy to death.

Hollywood then spread this mis-interpretation in its many "sword and sandal"

epics. I do not have any specific references I can refer to, other than

the evaluation of the Latin terms and what has been brought to light in recent years. The

"down-thumb - pollicis-demissus" or the thumb held down on top

of the closed fist meaning "to spare - mitto - let go of", and

the "turned-thumb - pollicis-vertit or pollicis deflectere",

with the thumb held toward the chest, indicating "to kill - necare"

(by cruel means) or

"caedere" (to inflict wounds or blows) are now becoming accepted as the signs that

were probably used in the Roman Arenas.

THE ORGANIZATION, TRAINING AND COMBAT OF GLADIATORS

Maximus and his "Lanista" Mirmillo and Retiarius Commander and Maximus at the Palus

Gladiatorial combat was not invented by the Romans, but Rome developed all the essentials and features of the system bringing it to the state of perfection it had reached by the First Century AD. Thus it can be said that gladiatorial combat, in its most developed form, was specifically a Roman form of competitive sport.

In the course of the First and Second Centuries BC, these warlike spectacles assumed such dimensions that they required a great deal of organization. Gladiatorial schools "Ludi Gladiatorium" were established throughout the Empire and Provincia; each run by a "Lanista", a private entrepreneur who acquired suitable men by purchase or recruitment, trained them and then hired them out to interested parties. Many of these Lanista were former veterans of the arena who had been honored with the presentation of the coveted "Rudis" (wooden sword) by the Emperor thereby earning their freedom and retirement from combat due to their prowess and popularity. The gladiators whose ranks also included condemned criminals and quite a number of volunteers "auctorati", lived in barracks and were subject to strict discipline. Their trainers aimed to achieve maximum physical fitness through a well-balanced diet, constant hard training and careful medical attention. The training itself was entrusted to "doctores" and "magistri", most of them probably former gladiators.

A "Galerus" shoulder shield, an arena style "Gladius" sword and a wood "Rudius" practice / award sword. The Galerus was the only armor worn by the "Retiarius". Note the wool pelt installed for comfort in the shoulder cavity. The arena style gladius was adapted from the Legionary gladius and was slightly shorter with a round metal hilt and wood grip without the usual large pommel found on the Legionary sword. The wood "Rudis" shown here represents the ceremonial wood sword that would be presented by the Emperor to a gladiator being retired from gladiatorial combat with honors. The Rudius was also termed a "waster" and was used for training, that is "waisted" for non-combat practice by gladiators and legionary soldiers. This Rudius has three brass plates bearing the following inscriptions: on the top of the pommel, "Oberon", the Commander's gladiatorial nomen (name) - on one side of the hilt, "Titus Flavius Vespasianus", the Emperor who presented him with the Rudius - on the other side of the hilt, "Kalends Martius 833 AUC", the first day of March or Roman New Year, 80 AD, when he was presented with the Rudis upon his honorable retirement from the arena.

The gladiators practiced in a small arena using blunt weapons "wasters" generally made of wood. They trained first with a stationary post "palus" and various moving obstacles and then later with an another gladiator as an opponent. This method of training and conditioning was also used in the army. The upper ranks of the paramilitary gladiatorial hierarchy were termed after these training posts and each category of gladiators had its own "Palus-Primus", Palus-Secundus" and so forth. Naturally the status and market value of a gladiator depended upon his success in the arena. Careful records were kept on his number of engagements, how often he won, lost, fought to a "draw" or had gained the highest distinction of all, the Laural Wreath.

The members of a gladiatorial "family" formed a "familia gladiatoria", usually named after its owner. In most public contests members of the same gladiatorial familia fought each other, so that if a duel ended in death it often a man's own comrade who had to deliver the fatal blow. At times, several Ludi-Gladiatorium (schools) would take part in a large spectacle and gladiatorial companies also went on tour. When gladiatorial combats came under State Control with the establishment of the Empire, the private schools continued in existence; but great Imperial Ludi were also set-up in the larger cities and provinces, managed by officials of knightly rank known as "Procuratores". From the late 1st Century AD onwards, there were no less than four Imperial Ludi in Rome, the most important being the Ludas Magnus beside the Flavian Amphitheater (the Colosseum). An underground passage linked the school directly with the holding areas beneath the arena (floor) of the amphitheater, so that the gladiators could travel to and from the Ludas Magnus School without being seen by the public. Once called to take their turn, the grim business of gladiatorial combat began, with the sounds of metal clashing, and the screams of agony from the wounded and dying, amidst the cheers of the crowd, who reveled in the spectacle of the carnage. While detailed accounts were kept of the number of animals killed in the contests; few records were made of the countless gladiators who died for the pleasure of the Emperor and the depraved masses.

Such was one of the Lessor Glories of Ancient Rome.

The gladiatorial games or "Hoplomachia" began with a grand feast for the combatants on the evening before their fights, to which the public were invited. The next day the gladiators would be driven in chariots or marched to the amphitheater where they were paraded before the cheering crowd. When they reached the imperial box or "Pulvinar", they addressed the Emperor with the famous chant "Ave Imperator; Morituri te Salutant!" - Hail Emperor; Those who are about to die Salute Thee! A variant was "Ave Caesar! Nos Moriruri te Salutamus!" Hail Caesar (Keisar)! We whom are about to die salute you!

The games commenced with a mock battle or "Prolusio" with dummy or padded weapons in the manner of a warm-up before the main event began in earnest. Individual fights were often interspersed with clowns and dwarfs parodying the real gladiator's battles or reenacting famous struggles from mythology, such as Hercules and Antaeus. Each pair of combatants would be selected by the "casting of lots" and to the accompaniment of trumpets, horns, drums and hydraulic organ, each duel took place. When a combatant capitulated it was the victor's right to choose whether his opponent was spared or dispatched. If the Emperor was present, the winner would defer to his judgment. The Emperor would frequently consult the opinion of the crowd. The winner received a palm branch for each victory; but he would have to earn many "palms" before being awarded the coveted "Rudis" or wooden sword which granted him freedom from the Arena with the title of "Rudiarii". Very few gladiators ever survived to enjoy retirement. The epitaph of one gladiator has come down to us, which tells how he was killed by an opponent whose life he had spared in a previous encounter. It concludes with a solemn warning to all who fought in these dreadful events. Moreo ut quis quem vicerit, occidat! - Give no quarter to the fallen, no matter whom he be!

A model of the Colosseum as it appeared in ancient times. The Colossus of Nero is just beyond the shadow edge toward the upper left. The Arch of Constantine is at the far left and the tapered column behind it is a water fountain known as the Sweating Pillar. The Ludus Magnus Gladiatorial School is at the middle far right. Nero's "Golden House" palace fills the upper right corner

Details on the Colosseum can be found on our COLOSSEUM Page

* HOME * TOP * ARMOR * WEAPONS * EQUIPMENT * ROME HISTORY *

* COLOSSEUM * LUDUS MAGNUS IN THE ARENA *

VIRES et HONOS - STRENGTH and HONOR

We of Legion XXIV Salute You for being the

to enter the Gladiatorium Academia